“That’s where Rillington Place was – terrible murders, so dreadful they had to change the name of the street…”

In general, I was never any great fan of crime stories, neither was I a student of murder mysteries, much less serial killers. My interest came from a different direction.

Having been born and spent my early years in North Ealing, it was a fairly frequent event to travel into central London via the A40 Western Avenue, later to include the elevated Westway section and, when travelling in the family car, my late father would gesture towards the grimy terraces close to the road as it passed through North Kensington and observe solemnly: “Down there, that’s where Rillington Place was – terrible murders, so dreadful they had to change the name of the street…”

A short distance from North Ealing was Park Royal – and to the southern side of the Western Avenue lay a shopping parade and the Underground station. In those days, grocery shopping was a more-or-less daily event as freezers, and even refrigerators, were still largely unknown to most ordinary families. To the northern side was (and remains) the Park Royal industrial park which, at 500 hectares, is London’s largest business and industrial estate. During the First World War, it was the location of numerous munitions factories, afterwards becoming an important industrial centre which also included the Middlesex General Hospital and such major factories as H J Heinz and the Guinness brewery – the aroma from which often pervaded the locality. From 1935, another large factory was that of Ultra Electric Limited which, with some 1,500 employees and an output of up to 1,000 units daily, manufactured domestic transistor radios including the one in daily use for many years at my family home.

This factory was also the place where, in early 1944, John Christie went to work as a driver after having been released, at his own request, from the War Reserve Police in December of the previous year – and where he met his second victim.

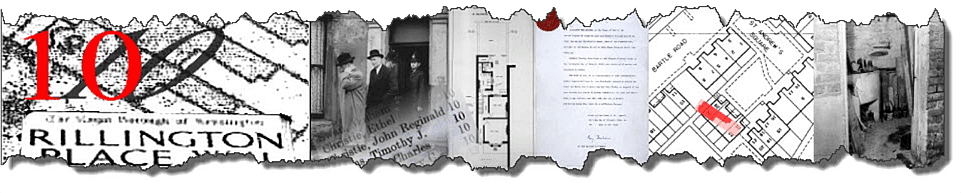

It will have been some time in the mid-sixties. I recall checking in the then-current issue of the Geographer’s A-Z Street Atlas of London and ascertaining that there was indeed no mention of a Rillington Place – but the street itself was clearly still there, but now named Ruston Close. Thus, the first glimmerings of an interest arose. There was Ruston Mews though, over the other side of the road, and surely the two must have been named at the same time mustn’t they? This in itself was puzzling as there was no suggestion that the latter had had any similar need to change its name, so how was it that the two streets opposite one another now shared a common name but after one of them had been changed? All would later become clear.

In any case what could have been so terrible that even the name of the street could not have been allowed to remain? I had never heard of such a thing before. At a tender age, and without so much as an encyclopaedia to refer to, let alone an Internet, it was difficult to pursue as by then even the old copy of the A-Z atlas had simply been discarded as out of date.

In 1970, the film starring Richard Attenborough in the role of John Christie was made and premiered in the UK in January 1971 (and on general release from May) but I would not have gone to see such a film at that time as it might not have seemed either all that suitable or of any great interest. In due course, perhaps a few years later, the film was shown on television for the first time, and that was the moment when, as a young adult, the whole subject came once again into my field of view.

The one great merit of the film for historical purposes is that it made use of the street itself for external location shooting – indeed its impending demolition in pursuit of slum clearance was reluctantly and briefly delayed in order to allow for filming to take place. Although tantalisingly few and short, the sequences that were captured do now allow for an impression of the area to be gained in a way that even the most faithfully recreated film set could never have done. It is also, of course, the nearest anyone can now come to actually seeing the street as it really was.

More years passed, and by this time I was pursuing a musical interest – playing in a band – and our rehearsals took place at a studio in Lots Road at the very southern end of The Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea. At the time I was living in Harrow and my route to and from the studio by car took me along the north to south routes through the Borough – mainly the A3220 Holland Road and Warwick Road. One fine day, probably as a result of having just seen the film again on television, I decided to satisfy at last my curiosity and take a detour to the very place itself. All that was required was a short diversion eastwards and a run up the length of Ladbroke Grove.

With somewhat quickened pulse as I drew near, the initial impression was both confusing and rather disappointing. It would have been 1978 and, as I now know, the modern developments of Bartle Road, St Andrew’s Square and Wesley Square had only just reached completion. I could see enough to know that I was in the right place – there was Ruston Mews, Andrews Garage and the railway bridge over St Mark’s Road – and yet nothing else looked right. Again, as I now know, this was entirely to be expected. One of the main design objectives of the new development was to obscure the old road layout as far as possible thereby preventing any one house, plot or location being blighted by being readily identifiable as occupying the exact place where the old house had once stood. Present-day residents who have lived there since the development was completed speak of how the developer and estate agents at the time stated that the site of the old house was the garden in between the buildings in Bartle Road – untrue, but easy to see why a developer would say so. Clearly this is the origin of one of the many myths surrounding the location.

The Local Studies section of the Kensington Central Library provided an essential collection of resources in the form of historical maps, electoral register records, press cuttings, period photographs and much other documentation. This was to prove vital in developing the whole wider account that was later to be undertaken – and thus began, at ten years and counting, the longest weekend’s work ever embarked upon.

Perhaps this book might best be described as the story of what happened to me when I resolved to find out . . .